Balit-dhan Balit-nganjin (Their Strength Our Strength) was designed in collaboration with Maree Clarke to commemorate an extraordinary story, the founding of Coranderrk, a reserve created by the Kulin Nations to serve as a foothold in the colonial economy and as a sanctuary for the Indigenous Australian communities of Melbourne.

The commodity crop of Coranderrk was hops, a flavouring agent used in the production of beer. The entire process was industrially managed at the reserve; from the hops bines to the Oast Houses, Coranderrk delivered a commercial product to the local market. At the height of hops production, around 1880, Coranderrk had at least seven commercial hops gardens and won a number of awards for the quality of its produce. The success of the Coranderrk hops farm brought autonomy, sanctuary and independence to those who lived and worked on the reserve and is evidence of the resilience of this community, quickly and against extreme adversity thriving in this colonial context.

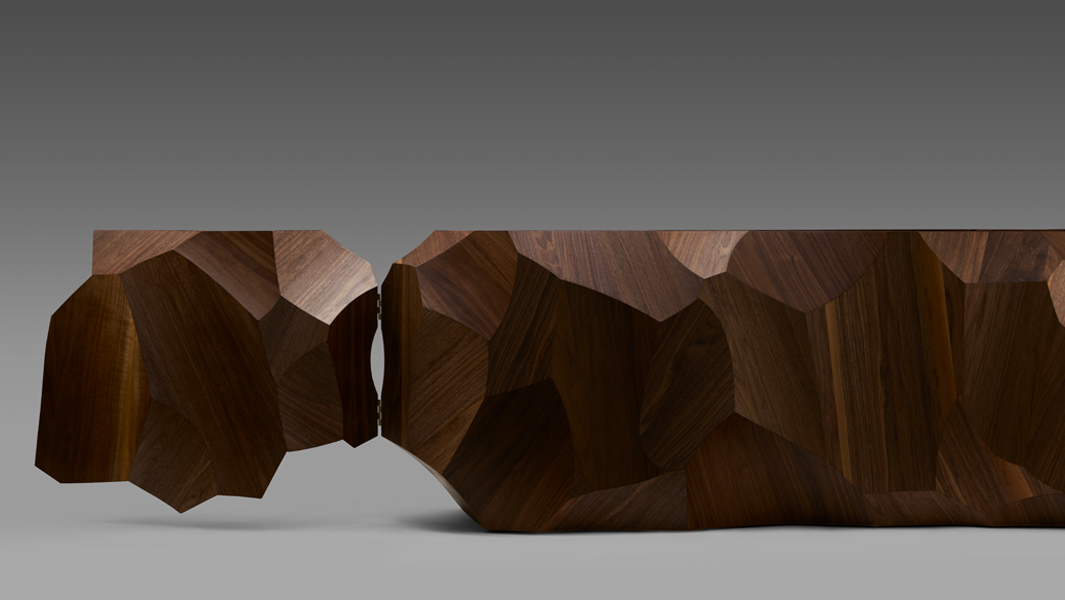

As part of this hops farming operation, members of the Coranderrk community cut 26,000 hops poles – long tree branches used to support the hops plant as it is grown vertically. This pole is an emotive and unmistakable symbol of hops farming on the Coranderrk Reserve as well as the ingenuity and toil of the Kulin Nation hops farmers who forged a livelihood for their community from this unlikely crop.

The original route taken by a group of forty people of the Kulin Nations into the Yarra Ranges and to the eventual site of the Coranderrk Reserve is known as the Black Spur. As the route of this great pilgrimage, the Black Spur has obvious historical and cultural significance, leading to a place where these communities were able to establish a degree of autonomy, sanctuary and independence that had previously evaded them post colonisation. To date, this journey has gone largely un-mythologised. We hope to change this.

The photographs of the Black Spur taken around this time depict a region of unchallenged Country. The vague suggestions of roads appear to be part of the flora, the edges blending seamlessly into bush, their contours matching the land, looking like they could be consumed by the scrub at any moment. This must have been a welcome site to those pilgrims seeking a place of sanctuary from the creep of colonisation. Here the Country was winning over the colonisers, and the relentless will of the bush could still be felt.

We see this stretch of road as historically and metaphorically significant to our two protagonists, William Barak and Louisa Briggs. As the track travelled to the formation of the Coranderrk Reserve, a path that provided their people sanctuary on their journey and a path along which to build dreams of their destination.

William Barak was a Wurundjeri man, an important patriarch of the Wurundjeri clan and the Kulin Nations. According to Uncle Larry Walsh, Barak found power at the eventual Coranderrk settlement in part because of the specific location of this settlement, on Wurundjeri land. This final location gave Barak influence over those from other communities, as the decisions made at Coranderrk were formed on the land of his ancestors, land that had been under the care and control of the Wurundjeri for countless generations, and land over which they maintained ultimate control.

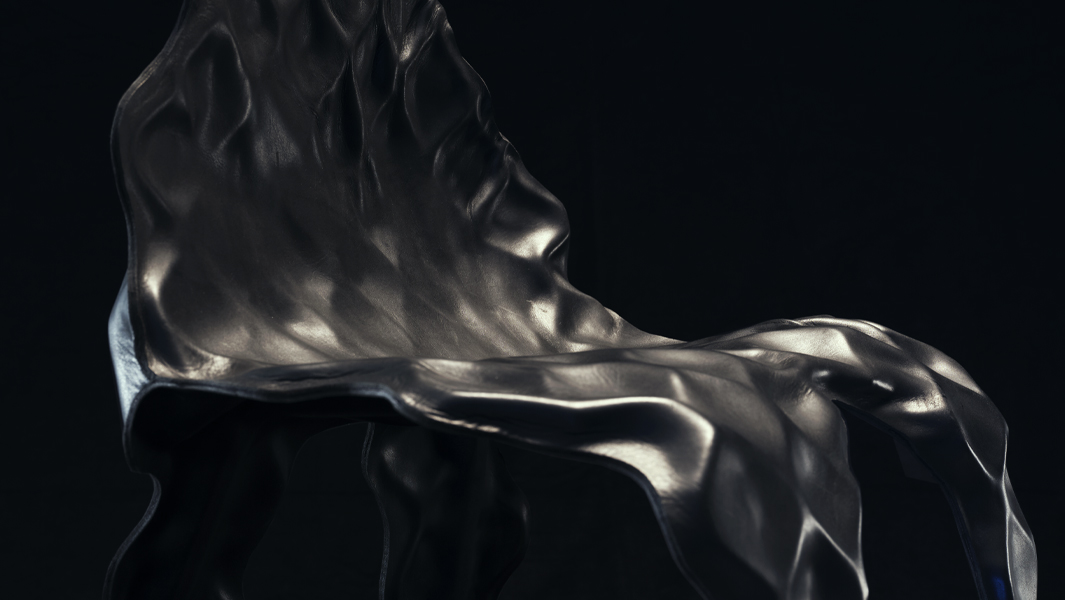

As an important patriarch of the Kulin Nations, Barak was given the privilege of harnessing fire. According to Maree Clark, fire sticks, along with the knowledge required to generate fire, was men’s business for the Kulin nations, and this right of access enhanced Barak’s power and influence over his community. Fire is also an element of importance to the journey the Kulin Nation clans made along the Black Spur in the months leading up to March 1863. According to Uncle Larry Walsh, this region of the Yarra Ranges is the site at which the Kulin Nations were first given fire by Bunjil, and as such, this important creation story would have been present in the thoughts and story-telling of those traversing the Black Spur during this meaningful pilgrimage.

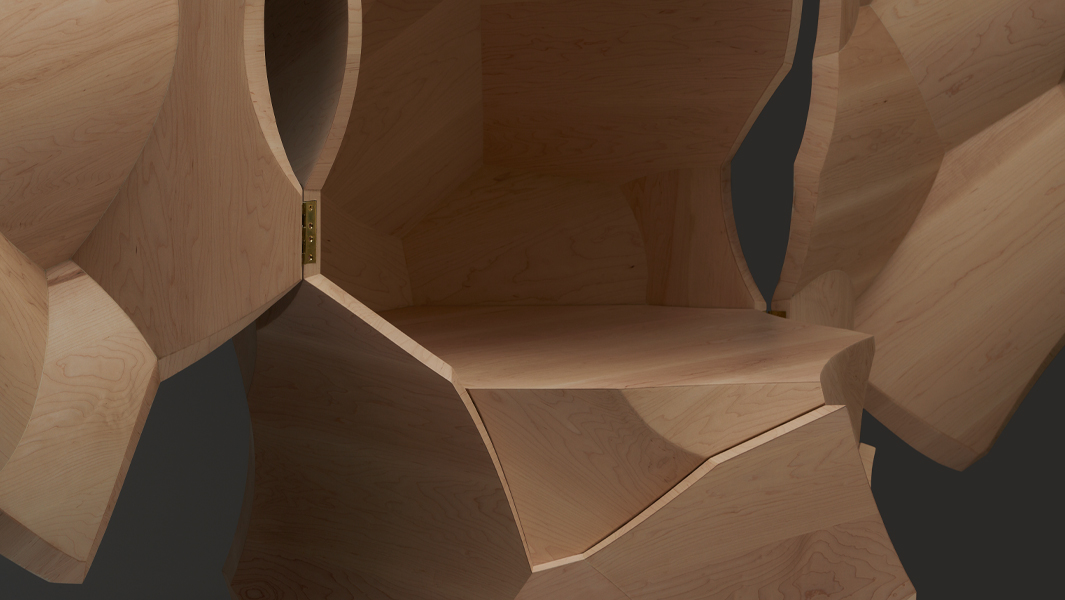

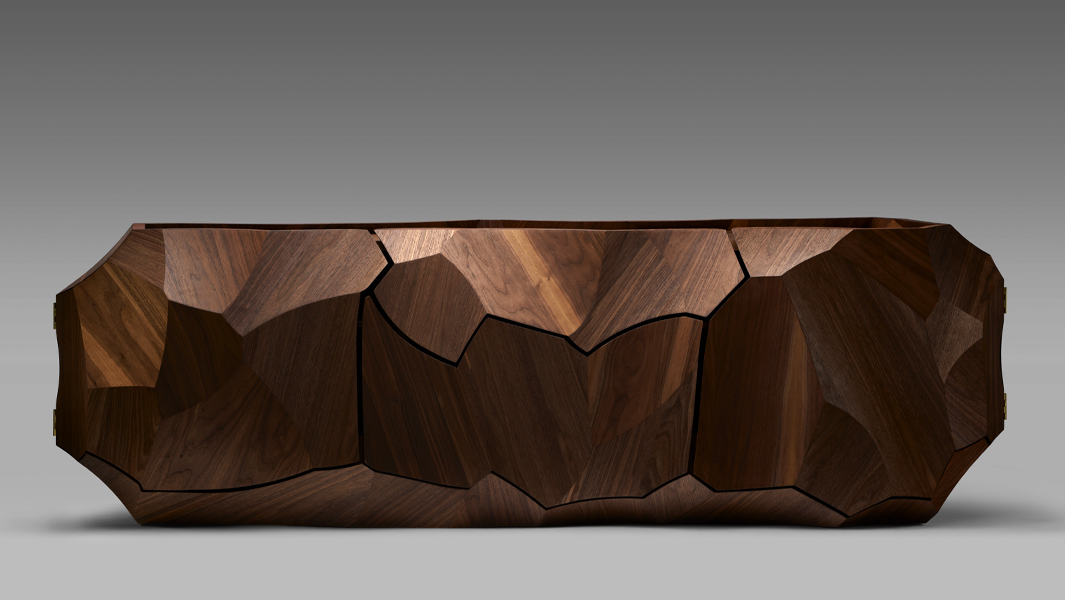

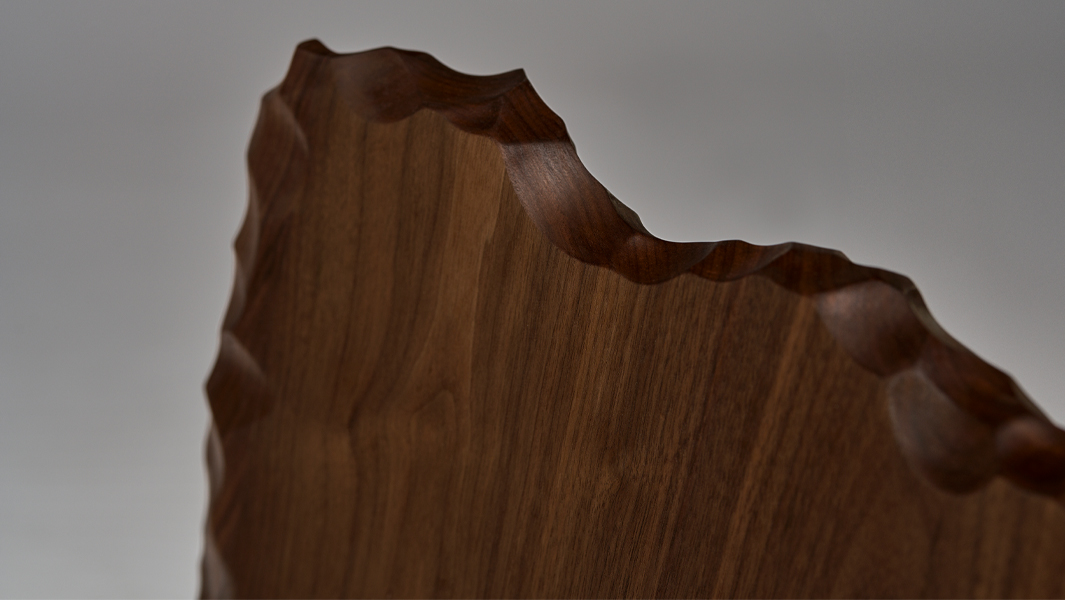

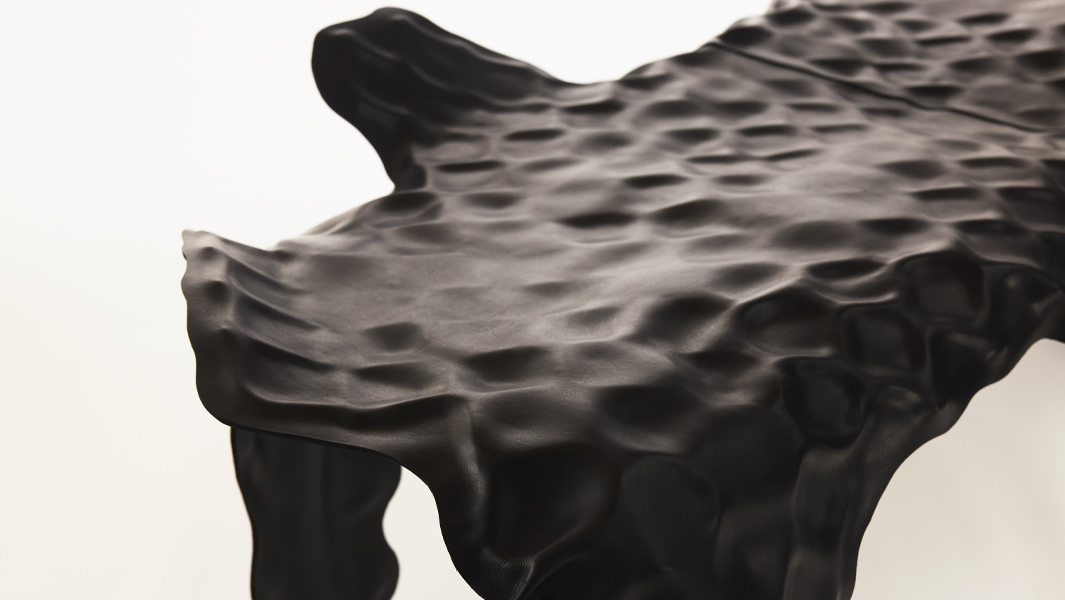

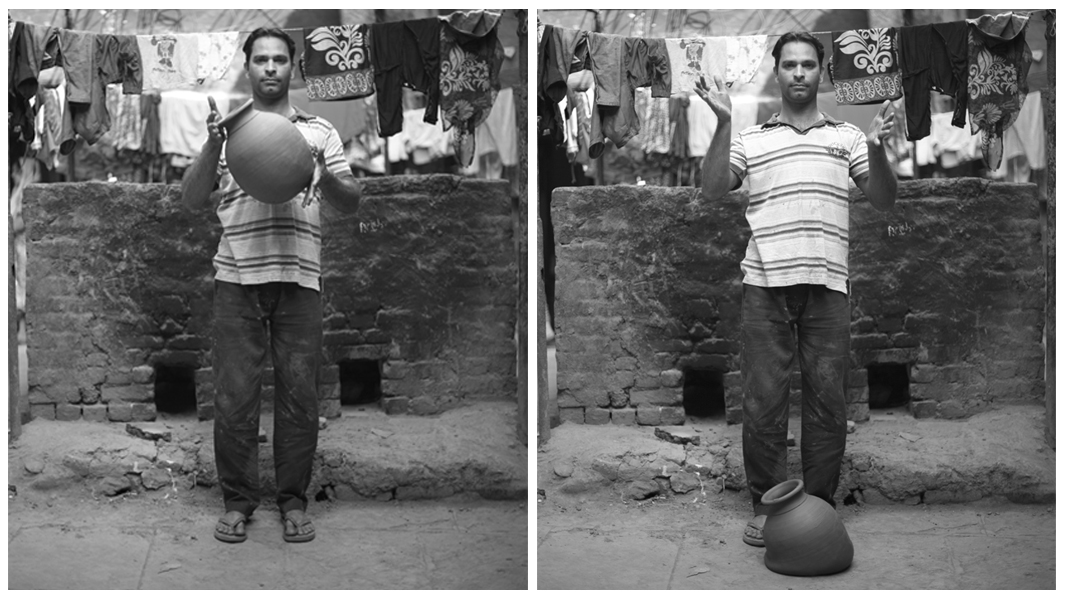

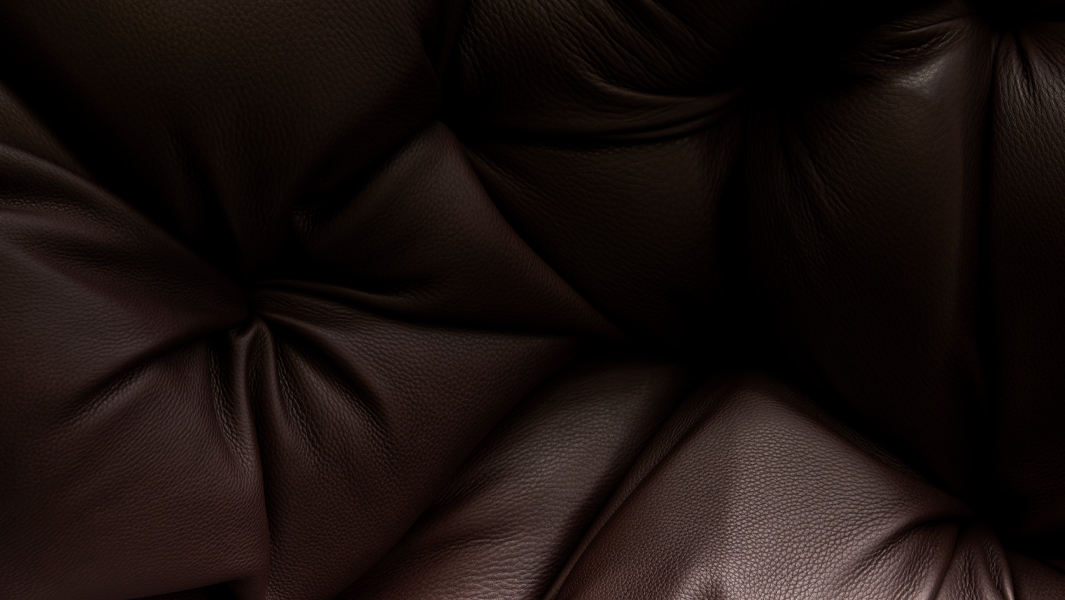

The texture of charcoal was used in one of the final bench designs to represent William Barak. The seat of this bench was constructed using fragments of charcoal and reproduced in a highly accurate lost-wax bronze casting process, registering every textural facet of the charcoal in bronze facsimile. A patina was then applied to the bronze, recreating the complex matt blacks, greys and browns of charcoal and adding to the visual texture of the seating surface.

Louisa Briggs was a matriarch of importance to the Boon Wurrung clan of the Kulin Nations, with family connections also to the Eastern Straightsmen and Trawlwoolway clan of north-eastern Tasmania, both through her mother, Polly Munro and her husband, John Briggs. Briggs had a complex life, working as a shepherd in the Beaufort district and a squatter near Violet Town during the gold rush. Between 1853 – 1871 Briggs and her husband John had nine children, and during the work scarcity which followed the gold rush Briggs and her family made their way to Coranderrk.

Briggs’ history at Coranderrk begins in 1874, when she worked as a nurse and dormitory matron and lead the community during rebellions at Coranderrk. In 1878, following her husband’s death, Briggs and her children were forced out of Coranderrk, only to return again in 1882. Again in 1886, Briggs and her family were exiled from the reserve, pleading with the board to allow her return, a request that was denied due to Briggs’ Tasmanian heritage. Between 1886 and 1925, Louisa made several unsuccessful attempts to return to Coranderrk, each time denied entry because of her Tasmanian heritage. Briggs died in September 1925, on the Cumeroonunga Aboriginal Reserve, on the New South Wales side of the Murray River, away from the community she so longed to be part of.

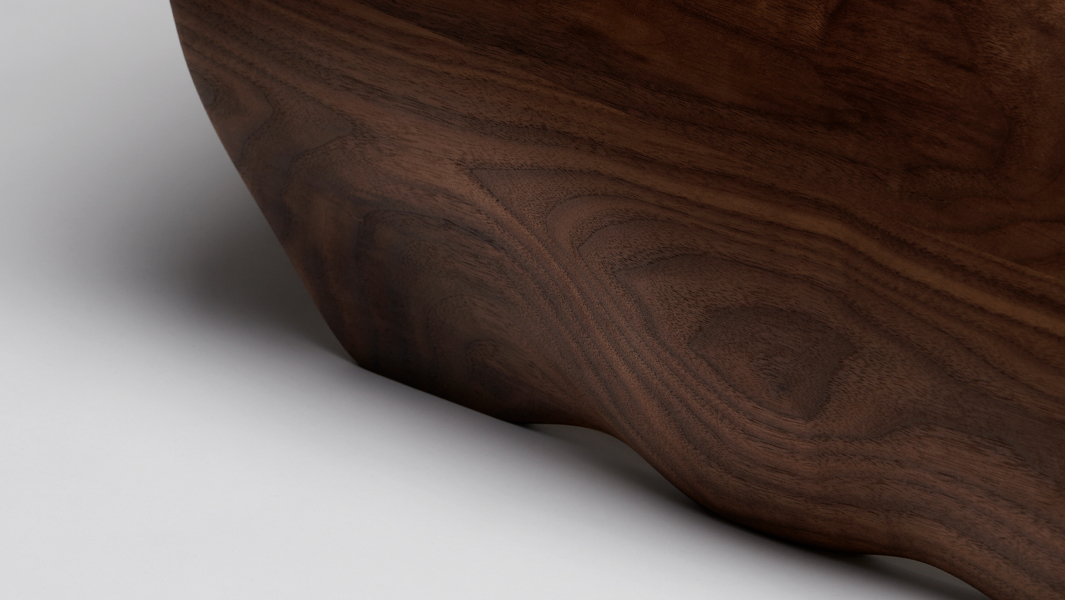

According to Maree Clark, the river reed bares significance to Briggs’ life as an important matriarch of the Kulin Nations. The construction of river reed necklaces was and remains an important women’s business tradition in this region, bestowed upon visitors to the area who had arrived from other communities, welcoming them onto Kulin Country for a predetermined period of time. The visitor was to wear the necklace at all times while on Kulin Country, as an indication of their status as a visitor, and so that no harm would come to them during their visit. Briggs was both welcomed at Coranderrk and exiled as an outsider, depending on the internal politics of the reserve in any given year. The river reed is a poignant symbol for Briggs’ tumultuous relationship with status and her ongoing struggle with welcome on Kulin Country.

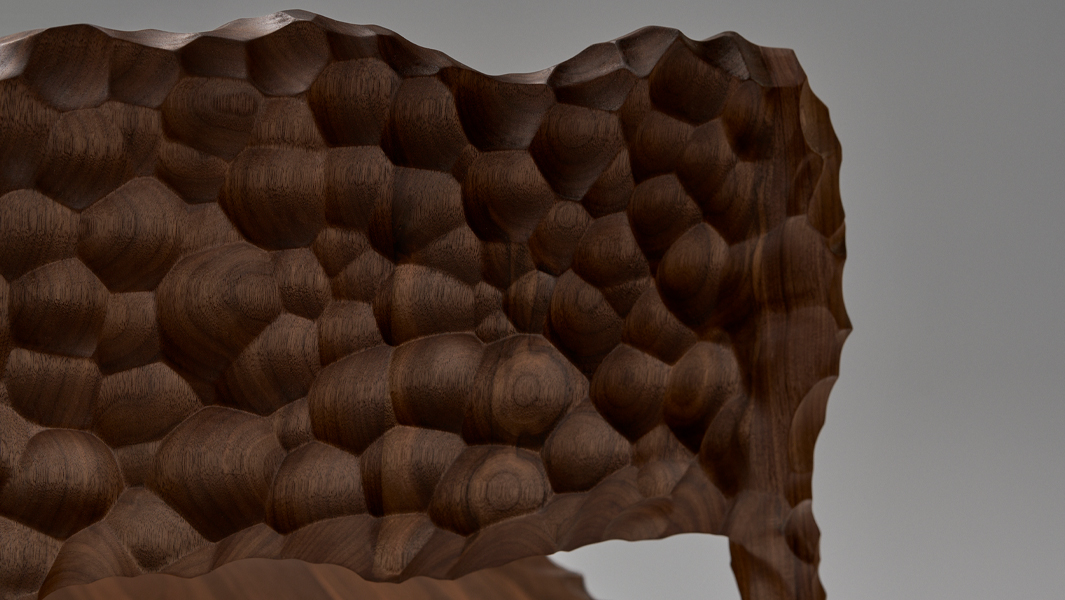

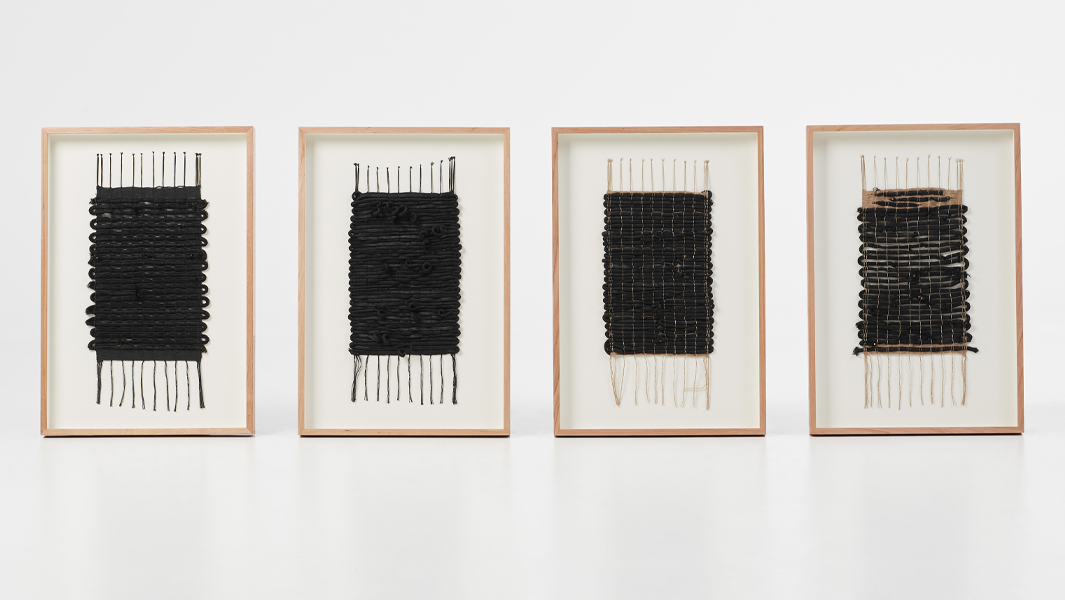

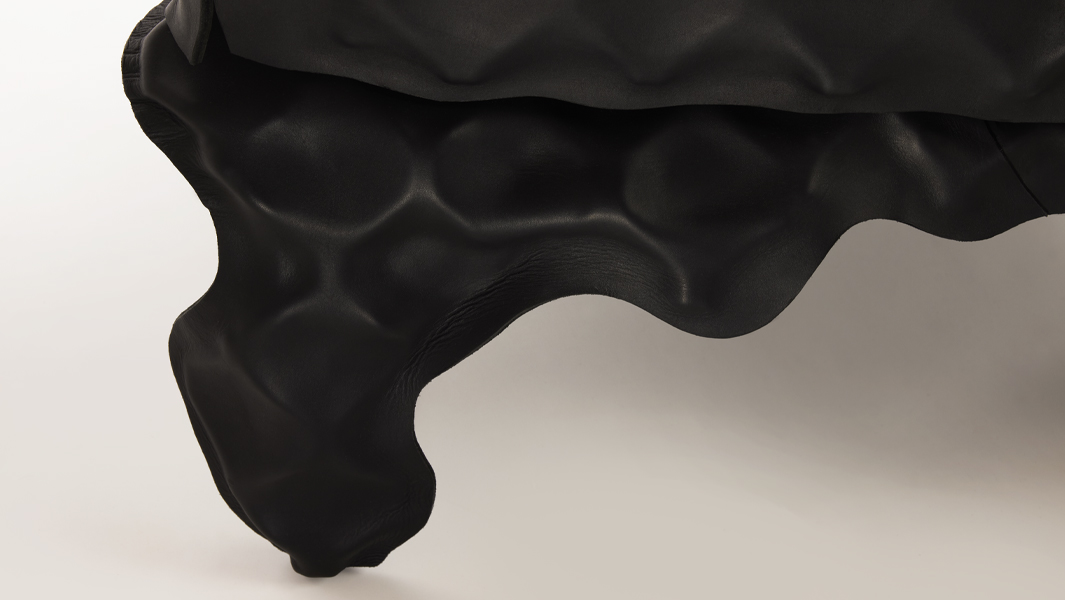

The texture of river reeds is used on one of the final benches to represent Louisa Briggs. The seat of this bench is constructed from cut sections of river reed, traditionally used to make river reed necklaces. This surface was reproduced in a highly accurate lost-wax bronze casting process, registering every textural surface of the river reeds in bronze. A patina was then applied to the bronze, reproducing the mottled colour palette of the reeds and adding to the visual texture of the seating surface.

Balit-dhan Balit-nganjin (Their Strength Our Strength) constitutes two sculptural benches, designer by Maree Clarke and Trent Jansen to commemorate the ingenuity, rigour and pragmatism of the Kulin Nations and their establishment of the Coranderrk reserve. The benches extract two fundamental elements of the community, its culture and economy: The seats of the benches represent both the river reeds that elders such as Louisa Briggs used to create necklaces, to be worn by guests onto country, and charcoal, a remnant of the fire given to the Kulin Nations by Bunjil in the Yarra Ranges and wielded by the men of the community, including key patriarch William Barak. The long, vertical uprights signify the poles on which the hops plant was grown. These elements represent the pragmatic, sophisticated, yet deeply traditional leadership exhibited by people such as William Barak and Louisa Briggs – both central to the Coranderrk story.

These seats convey the strength and vision of two great leaders and their economic and cultural aspirations for themselves, their families and their communities.

Where

Wesley Place,

130 Lonsdale Street,

Melbourne, Victoria

Commissioner – Charter Hall

Creative Direction and Production – Broached Commissions

Production – Axolotl and Crawford’s Casting

Image Credit – Dean Lever